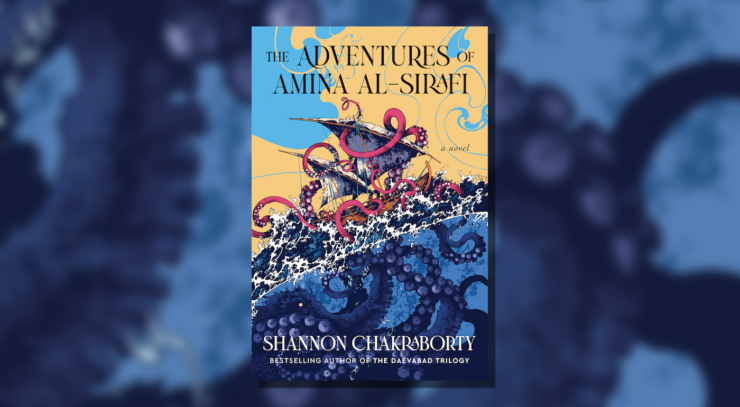

There’s always risk in wanting to become a legend… and the price might be your very soul.

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi, the start of a new fantasy trilogy from author Shannon Chakraborty—publishing March 7 with Harper Voyager.

Amina al-Sirafi should be content. After a storied and scandalous career as one of the Indian Ocean’s most notorious pirates, she’s survived backstabbing rogues, vengeful merchant princes, several husbands, and one actual demon to retire peacefully with her family to a life of piety, motherhood, and absolutely nothing that hints of the supernatural.

But when she’s tracked down by the obscenely wealthy mother of a former crewman, she’s offered a job no bandit could refuse: retrieve her comrade’s kidnapped daughter for a kingly sum. The chance to have one last adventure with her crew, do right by an old friend, and win a fortune that will secure her family’s future forever? It seems like such an obvious choice that it must be God’s will.

Yet the deeper Amina dives, the more it becomes alarmingly clear there’s more to this job, and the girl’s disappearance, than she was led to believe. For there’s always risk in wanting to become a legend, to seize one last chance at glory, to savor just a bit more power…and the price might be your very soul.

Chapter 5

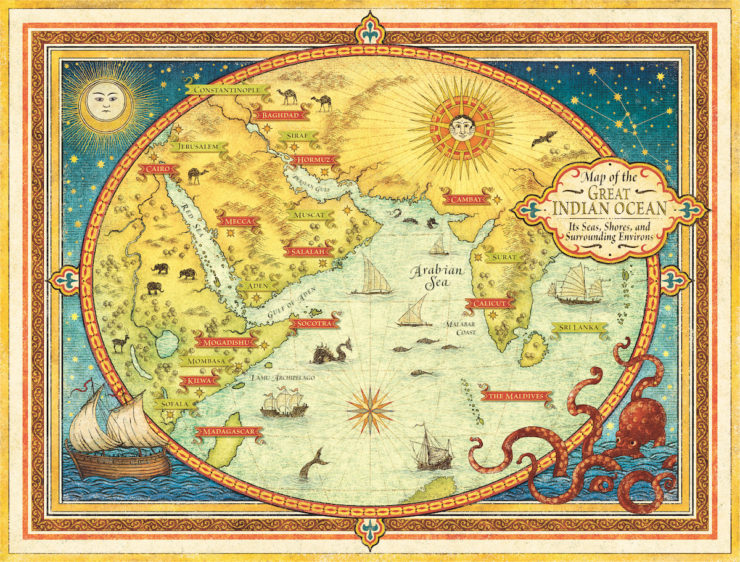

Ah, Aden. What can I tell a collector of tales about Yemen, that most glorious and blessed land, that they do not already know? I suspect you can spout plenty of verses extolling the wealth of the famed kingdoms of Saba and Himyar, and know by heart the epics of the warrior-king Sayf and his djinn companions in these lands. And at first blush, one might think Aden—Yemen’s most valuable pearl—would embrace the bewitching legend of its countryside. Perched upon the sunken crater of a long-dead sea volcano and ringed by jagged peaks that tear at the sky, the city’s very location seems out of a book of myths. There is but a single pass through the mountains, one said to have been carved by Shaddad bin ‘Ad himself during his conquests of the world before Islam. Curved around a bright blue bay, Aden gazes down upon its harbor like an eager audience in an amphitheater, with three forts, a new seawall, and numerous gates adding to its already fearsome natural fortifications. It is though the Almighty Himself decided to protect it. Sailing past its ancient breakwater—the stones said to have been set there by giants—it might feel as though you have entered a mythical port of magic from a sailor’s yarn.

You would be sorely mistaken.

Aden is where magic goes to be crushed by the muhtasib’s weights, and if wonder could be calculated, this city would require an ordinance taxing it. It is a den of number-crunching scribes, overly zealous accountants, and tax clerks who have you locked up if you so much as jest about bribes. There is money to be made for people like me: you can charge an excellent rate to smuggle goods around the city’s onerous customshouse. But to what end if there is not a tavern in which to spend your hard-earned coin and the only company to be found is with a bunch of law-abiding bureaucrats?

Dalila and I had chosen to make the trip overland and through the main pass rather than upon the sea, where those in charge of clearing travelers were more thorough (and by “thorough,” I mean they hire ladies who inspect everything). We had another reason for traveling discreetly as well. Though I couldn’t entirely blame Salima for how she approached me, Dalila had been less than pleased to learn how prepared the elderly noblewoman had been to reveal my location to my old foes. And by “less than pleased,” she called me a fucking idiot and went into a great harangue about risk management that convinced me she regularly murdered curious neighbors.

Nonetheless, by the time we arrived in Aden, we had a new plan. Salima was no doubt impatiently awaiting my arrival, but we would not go to her right away. Instead we would meet up with Tinbu and the Marawati and spend a few days taking the temperature of the city and inquiring after our mysterious Frank. Politics shift swiftly around here, and I did not wish to get caught in a situation unawares. For all I knew, Salima was working with the governor himself to set a trap for me.

Buy the Book

The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi

All right, yes, all that came from Dalila as well. See? This is why I recruited her first. Sometimes one needs a paranoid poisoner at their side.

As it was, we made it through the pass and into the city unbothered. I insisted on going to the Marawati straightaway, and as we strolled onto the beach I could not help but marvel at the difference a decade had made. One of the blessings of age is the waning of certain men’s eyes, of that stare that fixes upon you when you are a girl too young to notice. The men who do not lower their gaze as is commanded by our faith, but instead steal second and third glances; the men who hiss the vulgarest of obscenities and when called out, blame their behavior on your clothes, your smile or lack thereof, your pretty eyes, your very existence.

The men who always seem very surprised to be knocked on their ass and splitting bloody teeth when attempting such tricks on ill-tempered lady pirates. But happily past forty and dressed in the mended garments of fishwives, Dalila and I might have been invisible as we strode across the hot sand. We passed the seawall, and I paused to admire the unobstructed view of Sira Bay.

Aden’s harbor was gentle and the expanse of azure water—a sailor’s dream, clear of the coral and shoals that make most of the ports north of here so deadly—was dotted with about twenty ships, mostly the big sanabiq that carry trade goods to the East African and Indian coasts. A few more boats had been dragged onto the narrow beach for repairs, the muddy flats crowded with sweating laborers tightening hull stitches, making rope, and mixing sealant. The smell of coir and pitch combined with the salty breeze and reek of fish guts on the humid air to make a smell only a sailor could love. New mansions and promenades glistened in the distant hills, where their wealthy inhabitants could enjoy stunning sea vistas and pleasant breezes, but Aden’s newest construction boom appeared to have missed its poor: the palm frond huts on the sweltering beach—huts I spent a not-insignificant portion of my childhood in—looked as miserable as ever.

I fanned my face with the end of my turban as we made our way through a maze of wooden hulls, shark-oil–filled barrels, carpentry tools, lengths of rope, and flapping sails. The hot sand crunched beneath my thin sandals, and I was drenched with sweat in moments. Longing to spy my Marawati and plunge into the ocean, I stopped in the shade of a large sunbuq framed by stilts. Still, no one had bothered us. God, give us a couple tins and we could have boarded a ship claiming to be delivering food to hungry husbands and stolen it.

But I did not want any stolen ship, I wanted my stolen ship. I shaded my eyes, the sun’s glare upon the water fierce, and scanned the boats drifting in the bay.

“Do you see it?” Dalila asked.

“No. Though knowing Tinbu, she is likely nigh unrecognizable.” There is no one who knows his way around boats like Tinbu, my former first mate and the man who has been captaining the Marawati in my stead since I retired. He can break a ship down and build it anew in ways one would never imagine. “Look for similarly sized hulls.”

“Mama!”

On instinct, I turned and spotted a little girl running across the sand, her black braids bouncing behind her. Giggling, she crashed into a group of women mending nets and dropped to the ground, her hands full of oyster shells.

My heart panged. I was trying to preoccupy myself with work, but I could not go an hour without thoughts of Marjana, and the sight of any child made me ache. Was my daughter eating enough and staying safe? Did she miss me or had she gotten distracted in the blissful way of children? I watched the girl settle into her mother’s lap, the smiles exchanged between them driving a knife of loneliness through my chest.

“Amina.” Dalila tugged on my sleeve. “Can you see what is happening over there?”

I followed the direction of her glance. On the southern side of the harbor, closer to Sira Island, a group of people had gathered on the beach. There seemed to be some sort of commotion; their gazes were directed at the sea and excited chatter drifted our way. I glanced back upon the boats I had already examined thrice, but my Marawati was not there.

Nor did I like the energy of the growing crowd, an ill premonition knotting my belly. “Let us check it out.”

The crowd had gathered upon a sloping sand dune that made it difficult to see anything of the sea beyond glistening shards of water. I pulled the tail of my turban across the lower part of my face in case the years had not aged me into anonymity, and Dalila and I separated without a word, melting into the group.

“—think they shall find anything?” a man coated in wood dust whispered to his companion.

“Heard their throats were slashed to the bone, crabs crawling out of their mouths—”

I jostled past two boys, one hoisting the other to peer over the shoulders of the men in front of them. With an elbow to the ribs of a sailor and a rude shove to a matronly looking woman who let out an offended squawk, I was free of the mob with a clear view of the commotion.

And there, swaying in the gentle waves like a comely dancer, was my Marawati.

I praised God under my breath, my soul eased at the sight of my first love at, the ship I’d have cast all my ex-husbands overboard to save. She was a true beauty, India-made with a narrow hull of the finest dark teak. Her name was original, though I’ve little idea what it means; my grandfather was as cagey about the Marawati’s name as he was regarding the no doubt illegal way he obtained her. She was not overly large, but with a full complement of oarsmen and a deft hand controlling the vast sails and two rudders, she was one of the swiftest vessels on the sea, capable of fleeing far bigger warships.

Not that she looked like it at that moment. The oars and the rails that held them were nowhere to be seen, the decked platforms where we launched weapons were dismantled, and the rudder and stern ornaments had been changed. The hull and masts had been painted an ugly yellow-tinged green that looked like it needed to be refreshed twenty years ago, and between the fraying nets and rusty chains, the Marawati looked less like a speedy smuggling vessel and more like a fishing boat used to coast along the shore. The one thing Tinbu had not altered—my sole request—were the wooden rondels my grandfather had carved along the captain’s bench.

However, my eyes had barely settled on my beloved ship when said heart-easing abruptly ended. For you see, my Marawati was neither alone nor at peace. It was being actively searched by soldiers and pinned between two large—armed—galleys.

When… in the name of God… had Aden gotten warships?

“Two dirhams they find nothing,” a man behind me declared. “No one would be reckless enough to rob an Adeni vessel and then put in here for repairs.”

“I will take that bet,” another answered. “Never underestimate men’s carelessness. And whoever killed those poor souls was a monster. Such thieves have no such shame.”

“Nor do the two of you, gambling over the dead,” chided a third man. “God deliver us from such perversion.”

A triumphant cheer sounded from the Marawati; several of the soldiers hefting metal-hued ingots in the air. There was an indignant—and familiar—cry of protest, and then Tinbu, my most trusted first mate and sweetest of friends, was hauled out from the cargo hold.

I watched, my heart in my throat, as Tinbu was pushed before two figures in official-looking robes and turbans. Gesticulating wildly, my friend appeared to be arguing or perhaps pleading. I was not sure which option concerned me more. Tinbu is excellent at striking pacts with criminals, so practiced he forgets that civilian authorities occasionally have different responses to being bribed. The other men looked stern, their arms crossed over their chests. Tinbu raised his hands in an imploring fashion…

And was promptly smashed in the back of the head by a sword hilt.

He crumpled, and pandemonium broke out. A merchant-looking fellow in a striped blue and yellow shawl rushed to Tinbu’s side while around them, furious sailors threw themselves on the soldiers in a blur of fists. But the fight was over as quickly as it started, Tinbu’s band outnumbered. Aghast and helpless, I watched as they began arresting the crew, binding the men with ropes and shoving them toward one of the warships.

“Well.” Dalila reappeared at my side as though stepping out of an invisible realm. “This changes things.”

I pulled at my turban in despair. “Why are there warships?”

“Yes, that is also an unpleasant development.” Dalila clucked her tongue. “We will need to find an alternative way to travel.”

A pair of guards dragged Tinbu between them. I watched as he attempted to lift his head and was rewarded with a punch to his stomach.

An old, dangerous anger lit inside me. “We follow.”

“Amina, ‘we follow’ plays no part in obtaining very large sums of money for discretely—”

“No sum of money is worth such a loss to me.”

Dalila grunted in annoyance. “I knew he was your favorite.”

“I was talking about my ship. Now follow.”

***

Tinbu and his crew were marched directly to Aden’s prison, a former warehouse besides the muhtasib’s office. Whatever crime my friend was accused of must have been serious, for a crowd of onlookers awaited him at the prison as well. They were swiftly dispatched and replaced by a pair of baton-wielding soldiers who installed themselves outside the muhtasib’s door.

Fortunately the surrounding streets were busy, and so Dalila’s and my loitering was easy to miss. After so many years of isolation, I found the bustle of a proper city invigorating. I have always liked meeting new people and seeing new places, and quickly set to chatting up various vegetable buskers, leather workers, and a rather charming juice vendor who gave me a cup of pressed date nectar in exchange for the gossip I shared of the beach.

The juicer lowered his voice to a hush after my whispered recollection. “The wali is keeping it close to his chest, but rumors are a ship that normally carries pilgrims between here and Jeddah was smuggling iron ore and went missing a few weeks ago. Some say it was an accident and the boat must have broken up on the reefs, but others are claiming the bodies that washed ashore had their throats cut.”

“Pirates?” I clutched a hand to my chest. “So close to Aden?”

“Only God knows.” The juicer pursed his lips in annoyance. “The muhtasib is new and looking for any reason to seem important. But there is not much in Aden for him to crack down on save women visiting tombs and the occasional vendor letting their sugarcane juice ferment a bit too long. I imagine the prospect of murderous pirates, real or imagined, would be tantalizing.”

I liked this fellow. “Now, Brother, surely you are not suggesting a government official would invent such a heinous crime for his own amusement and career advancement?”

He blushed prettily above his salt-and-pepper beard, and I was reminded just how long it had been since I enjoyed a man. “God forbid.”

I winked, finished my drink and returned to Dalila. She had spread a mat on a patch of street that gave us a clear view of the prison, displaying a sad array of bruised fruit for resale that we’d bought in case anyone asked what we were doing.

“Done flirting?” she greeted, shooing away a pigeon.

“For now. How is business?”

“Poor. My boss is a fool who is wasting my time on a side venture when a riper prize beckons.” Dalila stabbed her knife into a melon, carving out a section and offering it to me on the blade. “That will be a million dinars.”

Taking the fruit, I asked, “Any updates?

“I have not heard screaming, so presumably he is not being tortured.” “

Tinbu would stay for you,” I pointed out as I squatted besides her.

“I would never require saving.”

There was little argument I could offer against that, so instead I studied the prison. It looked secure; the stone building had probably been here for at least a hundred years and its few windows were little more than narrow, barred slits. I had already scouted the perimeter, but a rear entrance was bricked over, leaving the guarded door as the only way in or out. We could tunnel below; we’d done so with similar buildings before. But tunneling took time and equipment, and we had neither.

I turned my attention to the nearby streets. This was a commercial neighborhood, crowded with workshops and offices, along with shops and food stalls that catered to hungry laborers and clerks needing to run errands before returning home. The closest mosque was distant, its minaret hazy above the maze of rooftops. In all, it seemed like the kind of place that emptied out at night. I rose on my toes to peer further down the street, and my gaze fell upon a foul scene. A young girl, barely older than Marjana, was being crudely examined by two men dressed in rich garments several buildings away. She wore a sackcloth tunic that skimmed her thighs, her hair hanging in loose, uncombed waves. One of the men motioned for her to open her mouth so he could check her teeth, the other squeezing her belly as though evaluating a fatty piece of meat. I hissed.

Dalila glanced up to see what had earned my ire, and her expression grew stormy.

“Hypocritical bastards,” she said in disgust. “Those men would probably die of shame before allowing their wives to take a lover, but force yourself on a girl who has no say because you bought her and suddenly all is fine and permissible before God.”

“I do not believe that,” I said firmly. And I don’t. Slavery is an abomination, no matter what excuses we find for it. There are people who will say the Quran allows such bondage; that many slaves are sold by their own parents and leave primitive, famine-struck villages for lives of ease and advancement in palaces and mansions and the enlightenment of God. I wonder how many such defenders have spoken to those enslaved?

Because I have. My crew has never consisted of less than a third freemen, and they have more horror stories than pleasant memories. I have stowed away girls whose hands were still wet with the blood of masters who raped them and seen lash scars on sailors’ backs so bad they can no longer move without pain. And yes, I know what the Holy Book says—but does it not also tell us to use our eyes and our hearts? How can one say Paradise lies under the feet of a mother if one may steal away the child in her arms?

Dalila touched my hand—I had reached for my dagger without meaning to. “You cannot save them all.” Indeed, the men were already exchanging coins and leading the girl away. “Dunya, Amina. Tinbu.”

Tinbu. Another who had been enslaved, taken captive in a raid when he was a teenager. My friend was a cheerful, lighthearted man, but he rarely spoke of those years, and I could only imagine how he felt now, shackled again.

I dropped my hand with a curse. Dalila was right. I couldn’t save everyone, but I would be damned if I left Tinbu in prison. “Does that mean you’ll help me break him out?”

Dalila made a sour face. “This is probably a trap.”

“You think everything is a trap. Perhaps God has placed us here on purpose.”

“If you are naïve enough to believe that, I would like to go back to my workshop.”

Raised voices came from inside the prison.

“I am telling you Tinbu was not involved in such a heinous crime!” It was the man in the striped shawl who had rushed to Tinbu’s side on the boat. A soldier was escorting him forcefully to the door, followed by an older man in officious dress. “You cannot charge him without proof!”

“What we can or cannot do is not your concern,” the older man rebuked. “Were he Jewish, he would be released to your community to handle. As he is not, I will get the answers I need.” He lowered his voice. “Think of your family’s reputation, Yusuf. Steer clear of this.”

They shut the door in his face.

The man—Yusuf—stood there, wringing his shawl. He was thin, his skin the pale brown of a man who did not spend his days toiling in the sun. His clothes were of fine flax, the hems embroidered with dancing hares in silver thread, and his beard tidily groomed. A well-off man, from one of the Jewish merchant families that has long held prominence in Aden, if I had to guess. He looked about a decade younger than me and if he wasn’t traditionally handsome, there was an earnestness in his green eyes I suppose would be endearing if that was your type.

It was not mine—I make terrible decisions and thus prefer men with a bit more mischief which has only ever turned out well. But I knew another who preferred his paramours sweet and soft, and so when Yusuf stalked away, looking heartbroken and miserable, I met Dalila’s gaze and we rose wordlessly to our feet.

We followed him through Aden’s narrow winding streets, deep into the city and through the pleasanter parts that rose away from the humid beach and busy market. Here the homes were larger: stone mansions with windows and doors framed in lovely intricate designs of whitewash, their interiors so thickly perfumed that the smell of frankincense and bakhoor scented the neatly swept avenues. The adhan rang out, the muezzin calling for maghrib prayer and we took advantage of the knots of men strolling from the pavilion overlooking the harbor to the city’s main mosque.

Yusuf was not behaving as though he suspected he was being followed. He turned down a skinny lane that cut between two buildings so tall they blocked what remained of the sun’s dying light. A quick glance revealed no windows and no other passersby.

“Wait here,” I whispered. Dalila fell back, stationing herself casually at the foot of the lane, and I hurried forward, affecting my best weary stoop.

“Sir!” I cried. “Please, might you spare a coin for a hungry old woman?”

Yusuf sighed but stopped to reach into his purse. Oh, bless him. “I do not have much, but—”

I was there the next moment, my dagger at his throat.

“Do not scream,” I warned. “I have no interest in harming you, but if you cry for help, by the time it arrives, you will be dead, and I will be gone.” I shoved him forward, deeper into the shadows. “Walk.”

His eyes burning with indignation, Yusuf nonetheless obeyed. I waited until there was no possibility of being overheard and his back was against a wall before I dropped the dagger a fraction away from his throat.

“Tell me of Tinbu,” I demanded.

Yusuf drew up with a furious, outraged air. “Who are you?”

“I am asking the questions. Is Tinbu hurt?”

His glare did not lessen, but he answered. “Tinbu is alive. He took a nasty blow to the head and seems confused, but that has not stopped their interrogations.”

“And what exactly are they interrogating him about?”

“He was caught carrying iron ore he found in the shallows north of here. The authorities claim it belonged to a ship that went missing several weeks ago. The ship has yet to be recovered, but the bodies of some of the passengers washed up. What was left of them anyway,” Yusuf clarified, going pale. “The wali says they were murdered.”

So it was as the juicer said. Damn. “Do they intend to charge Tinbu?”

Trembling, Yusuf nodded. “With murder and brigandry.”

My heart dropped. Murder and brigandry were the most severe charges that could be levied against my kind. Piracy is a tricky, complicated business in these parts. The merchants and princes who rain curses upon our heads are often the very same ones who hire us to protect their ships, smuggle them through customs, and steal from their competitors. I have never met a sea-thief who relishes ending a human life, if not for the sin of it then for the risk of punishment beyond a fine or brief stint in the stocks. Too much death and we were a scourge to be eradicated instead of a business resource. Taking to the sea is terrifying enough. Should you step out of line, there is no authority who won’t hesitate to make an example out of you.

And the examples… they are gruesome. The punishment for murder and brigandry, for “cutting the sea lanes,” is crucifixion, bisection, and having what’s left of you hung at the city gates. It has been the punishment since the time of the Romans, if the stories are to be believed, and perhaps even longer.

“Did Tinbu confess to illegal salvage?” I asked, recalling his pleading on the Marawati just before getting knocked out.

“Not at first. He, ah… suggested that if he could not account for the iron ore’s past, perhaps they might all agree to share its future.”

I groaned. “The fool has cut his own throat.”

“But he did not kill those men! I know Tinbu, and he is no murderer. I mean, he does not always conduct himself strictly within the law but…” Suspicion stole back into Yusuf’s voice. “Why are you asking me these things? Were you involved with these men’s deaths?”

“Not in the slightest. I too am a friend of Tinbu’s and hoped to recruit him for a job. A job that he has already put at risk, which is remarkably fast even for him.” I pinched my brow. “Are his men being charged as well?”

“I do not know. From what I gather, the wali is keeping them locked up without food and water while they consider their loyalties.”

Wonderful. A friend accused of murder and a crew of thirsty men. “And what of those galleys in the bay?”

Yusuf’s expression turned sourer. “They are new. The governor thought warships would make for a good deterrent after the pirate attack a few seasons ago. Raised our taxes only to use them for personal pleasure cruises thus far.”

Unsurprising yet promising—perhaps the men who manned them were novices at sea fights. “What kind of soldiers do they carry?”

“Some Mamluks imported from God only knows where. I could not understand the language they were speaking amongst themselves on the ship.”

“And what shape is the Ma— is Tinbu’s ship in?” I asked, correcting myself. “Is she seaworthy?”

Yusuf blinked. “I have no idea, I’m not a sailor. I know Tinbu brought her ashore for repairs a couple weeks ago, but he has not started loading cargo for his next trip yet.”

That was both good and bad news. The Marawati would be light, but for all I knew the sails were full of holes and the oars traded away for supplies.

But no… that wasn’t Tinbu’s style. He was reckless with officials, never with ships. No one with as many years as he had on the ocean was reckless with ships. There was a reason I had placed the Marawati in his hands.

I would have to pray he had earned it.

However, there was still the matter of getting him out of prison. “The wali and the muhtasib… Do you believe they’ll act swiftly?” I asked.

Yusuf had returned to worrying his shawl. “Yes. They seem to genuinely believe they have their man, and even if they did not, he’s an unbeliever who makes for an easy scapegoat. They will make fast, awful work of him to put other travelers’ minds at rest.”

“What news?” Dalila asked.

Yusuf jumped. “Oh God, there’s another one of you.”

I gave her a grim look. “Tinbu is being charged with murder and cutting the road and is shortly to be tortured and executed.”

“Ah.” Dalila’s voice was blunt. “Then I reiterate my earlier point. We need another ship.”

“And I will reiterate my earlier point: we are not leaving him behind.”

Shocked hope blossomed in Yusuf’s eyes. “Are you saying you can help him? Do you have evidence to prove his innocence?”

Evidence to prove his innocence… oh, but this man did not know the seafarer he was defending so ardently. “Who are you to him?” I prodded. Yusuf blushed, instantly confirming my suspicions. “I am one of his clients. He has been carrying cargo for my family to Calicut for a few seasons.”

“And you defend all your contractors with such ferocity?”

The blush deepened. “We have become friends.”

Oh, I bet. “Does that friendship extend to risking yourself to save his life?”

The merchant hesitated. “I would have to remain anonymous—I cannot put my family in harm’s way—but I will do what I can.”

Dalila grabbed my wrist. “You cannot seriously be considering this. Breaking a man out of prison is the exact opposite of ‘being discrete.’ We will have to flee Aden. Salima—the woman who can track down your family, remember?—will be furious. And any information we might have learned here will be gone.”

“Do you think I don’t know that?” I snapped. The promises I made to Marjana, to my mother, to Salima were ringing in my head… and yet to leave Tinbu to such a fate was unconscionable. “We will find another way, we always do. But right now, we’re getting our friend out of prison, and I’m getting my ship back from those fucking Mamluks in the bay.”

“Your ship?” Yusuf seemed to take me in anew, his eyes tracing my height and then going very, very wide. “By the Most High… they say her first mate was an Indian, but surely you cannot truly be—”

“No, surely I cannot. Let us leave it at that, yes?”

Yusuf opened and closed his mouth. “All right.”

“Excellent.” I glanced at the darkening sky with apprehension. I’ve never liked swift action. A proper job takes time to plan. The best take weeks of preparation for but a few hours of action. But Tinbu did not have weeks. I doubted he even had days.

I thought fast, contemplating my options. “Dalila, my light, do you remember the gold market in Kilwa? Could we get those materials in an hour?”

Dalila crossed her arms, giving me a severe look. “Obtaining those materials is not the same as blending them, and I have yet to agree to this idiocy.”

“Oh, for God’s sake, I will give you another percentage of my share, alright? Is there enough time?”

“Theoretically. The mixture does better when it’s had a full day to simmer.”

“If we wait a day, you will have to row instead of the crew.”

She made a face. “Fine. But we have no elephant.”

“We will make do with another distraction.” I glanced at Tinbu’s merchant, who was looking at us as though we had gone mad. “Yusuf… how is your acting?”

Excerpted from The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi by Shannon Chakraborty. Copyright © 2023 by Shannon Chakraborty. Reprinted courtesy of Harper Voyager, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.